Understanding PDA

Persistent Drive for Autonomy

This page brings together a range of helpful handouts, webinars, and information to support a deeper understanding of PDA (Persistent Drive for Autonomy).

The resources shared here are grounded in lived experience, neuroaffirming practice, and a compassionate understanding of PDA as a nervous-system-based response to perceived pressure or loss of autonomy. They are designed to support neurodivergent people, parents, educators, and professionals to move away from behaviour-focused approaches and towards safety, connection, and regulation.

Whether you are just beginning to learn about PDA or looking to deepen your understanding, we hope these resources offer clarity, reassurance, and practical support.

Persistent Drive for Autonomy (sometimes referred to as Pathological Demand Avoidance) is not a behaviour problem, a parenting issue or a lack of resilience. PDA is a nervous system survival response to pressure or ‘threats’ to autonomy, safety, predictability, dignity and connection.

For individuals with a PDA profile, demands and pressure are experienced at a nervous system level as threat. When threat is detected, the nervous system moves into survival states such as fight, flight, freeze, or shutdown.

Support must therefore focus on reducing threat, not increasing compliance, while always supporting nervous system regulation.

Persistent Drive for Autonomy (PDA)

Watch the Free: Understanding PDA Webinar

Understanding PDA: A 20-Minute Webinar

This short webinar offers a clear, compassionate introduction to Persistent Drive for Autonomy (PDA) and what it can look like in everyday life.

You can watch it right here.

Understanding Fluctuating Capacity

A central feature of PDA is fluctuating capacity. Capacity is not fixed, and it cannot be accurately understood by looking only at behaviour, attendance or willingness.

As pressure, demands, sensory load, social stress, unpredictability and loss of autonomy build up on the nervous system, the child’s window of capacity begins to close. When this happens, we often see changes in:

toileting

feeding

sleeping

self-care

sensory of safety

communication

These changes are not regression or refusal. They are signals that the nervous system is overwhelmed and operating in survival mode.

For example, a child who previously managed toileting, eating, or verbal communication may temporarily lose access to these activities of daily living when capacity is reduced. This does not mean the ‘skill’ is gone. It means the nervous system does not currently have the safety or regulation required to access it.

Areas of Change in Detail

When capacity is reduced, changes in these areas are common and predictable responses to nervous system overload. They are not behavioural choices and should not be treated as such.

Toileting

Changes in toileting are a frequent signal of nervous system overload. This may include constipation, withholding, accidents, increased urinary frequency, recurrent UTIs or avoidance of toileting environments. Stress and threat directly affect gut motility, pelvic floor coordination and interoceptive awareness. Toileting difficulties are often one of the earliest indicators that capacity is closing.

Difficulties with washing, dressing, brushing teeth, or tolerating everyday self-care tasks often increase when the nervous system is under sustained threat. These tasks require sequencing, motor planning, interoception and capacity for sensory input. When capacity is low, these demands can become overwhelming, leading to avoidance or distress.

Self-Care

When capacity is reduced, feeding can become increasingly restricted. Children may eat less, rely on a smaller range of safe foods, experience nausea or gagging or meet criteria for ARFID. Eating requires a sense of safety, regulation of the autonomic nervous system and capacity for sensory input. Loss of appetite or increased restriction is a nervous system response, not oppositional behaviour.

Feeding

Sleep is highly sensitive to nervous system state. Increased night waking, difficulty falling asleep, early waking, nightmares or inability to sleep alone can all emerge when the nervous system is in survival mode. Without adequate restorative sleep, capacity continues to narrow, creating a reinforcing cycle of exhaustion and dysregulation for the whole family.

Sleeping

As capacity closes, children may become more hypervigilant or seek safety through behaviours such as hiding, running, bolting or staying close to trusted adults. Some children may engage in head banging, self-injury or risk-taking behaviours as attempts to regulate overwhelming internal states or regain a sense of autonomy. These behaviours signal distress, not intent.

Sense of Safety

Communication often changes significantly when capacity is low. Children may speak less, rely more on gestalts, scripting, echolalia, gesture or behaviour to communicate, or withdraw altogether. This is particularly relevant for gestalt language processors. Reduced communication reflects reduced access to language under threat, not unwillingness to engage.

Communication

These changes are adaptive responses to an overwhelmed nervous system. When safety is restored, pressure is reduced, autonomy is honoured and regulation is supported through co-regulation and unconditional positive regard, capacity can reopen and access to these activities of daily living can return.

What Opens The Window of Capacity

Capacity begins to reopen when pressure is reduced and safety is restored.

This requires:

identifying pressures and demands that can be reduced or removed

creating environments that feel predictable and emotionally safe

honouring autonomy and consent

listening to the child’s communication in all its forms

supporting regulation through co-regulation and modelling

maintaining unconditional positive regard

Most importantly, capacity reopens when the child experiences that their communication changes outcomes and that connection remains intact even when they cannot cope.

Honouring autonomy while supporting the nervous system is not permissive. It is protective.

Our PDA Services

Our Services

We offer a range of supports for children, young people, families, and professionals supporting individuals with a Persistent Drive for Autonomy PDA profile.

All services are grounded in neurodiversity-affirming, trauma-informed, child-led practice. Our focus is on emotional safety, regulation, autonomy, and connection rather than compliance or behaviour change.

-

Online parent consultations offer a supportive space for parents and carers of children with a PDA profile to explore their child’s needs in a calm and validating way.

These sessions are led by Sorcha Rice, Senior Occupational Therapist, and focus on understanding your child’s nervous system, sensory profile, emotional regulation, and autonomy needs.

Parents often use these sessions to discuss daily challenges, school experiences, healthcare interactions, or to better understand PDA-affirming approaches. Following the consultation, families receive a short written summary with tailored recommendations to support safety, predictability, and regulation at home and school.

-

Our child-led sensory assessment is designed specifically with PDA and neurodivergent children in mind.

This assessment is low demand, relationship-focused, and centred on the child’s sense of safety and autonomy. It is not a test. Instead, it is a collaborative exploration of how your child experiences the world.

The process focuses on sensory preferences, regulation patterns, communication styles, and what helps your child feel safe and connected. The assessment includes parent input, optional school collaboration, a play-based observation, and a comprehensive written report with practical, PDA-affirming recommendations.

-

Child-led sensory groups offer a gentle, supportive environment for children with PDA profiles to explore sensory input through play, connection, and autonomy.

These small groups focus on co-regulation rather than performance or targets. Children are supported to engage at their own pace, follow their interests, and experience sensory input in a way that feels safe and predictable.

For many children with PDA, sensory groups can be a more accessible and regulating option than traditional one-to-one therapy.

-

One to one occupational therapy is available following assessment and places are limited.

These sessions are highly individualised and led by Sorcha Rice, Senior Occupational Therapist. Therapy focuses on sensory regulation, emotional safety, autonomy support, and co-regulation.

Sessions are child-led and build on the child’s strengths, interests, and communication style. The aim is to support participation and wellbeing without increasing demand or pressure.

-

We provide PDA-affirming training and consultation for schools supporting students with a Persistent Drive for Autonomy profile.

This work focuses on helping school staff understand PDA as a nervous system response rather than behaviour, and on creating environments that reduce threat, increase predictability, and support regulation.

Training may include understanding demand sensitivity, supporting autonomy, reducing escalation, and building trust and emotional safety in the classroom.

-

We offer training for professionals working with neurodivergent children and families, including educators, therapists, and healthcare professionals.

Professional training draws on lived experience, occupational therapy knowledge, and current neurodiversity-affirming practice. It supports professionals to move away from compliance-based approaches and toward relational, regulation-focused support for PDA profiles.

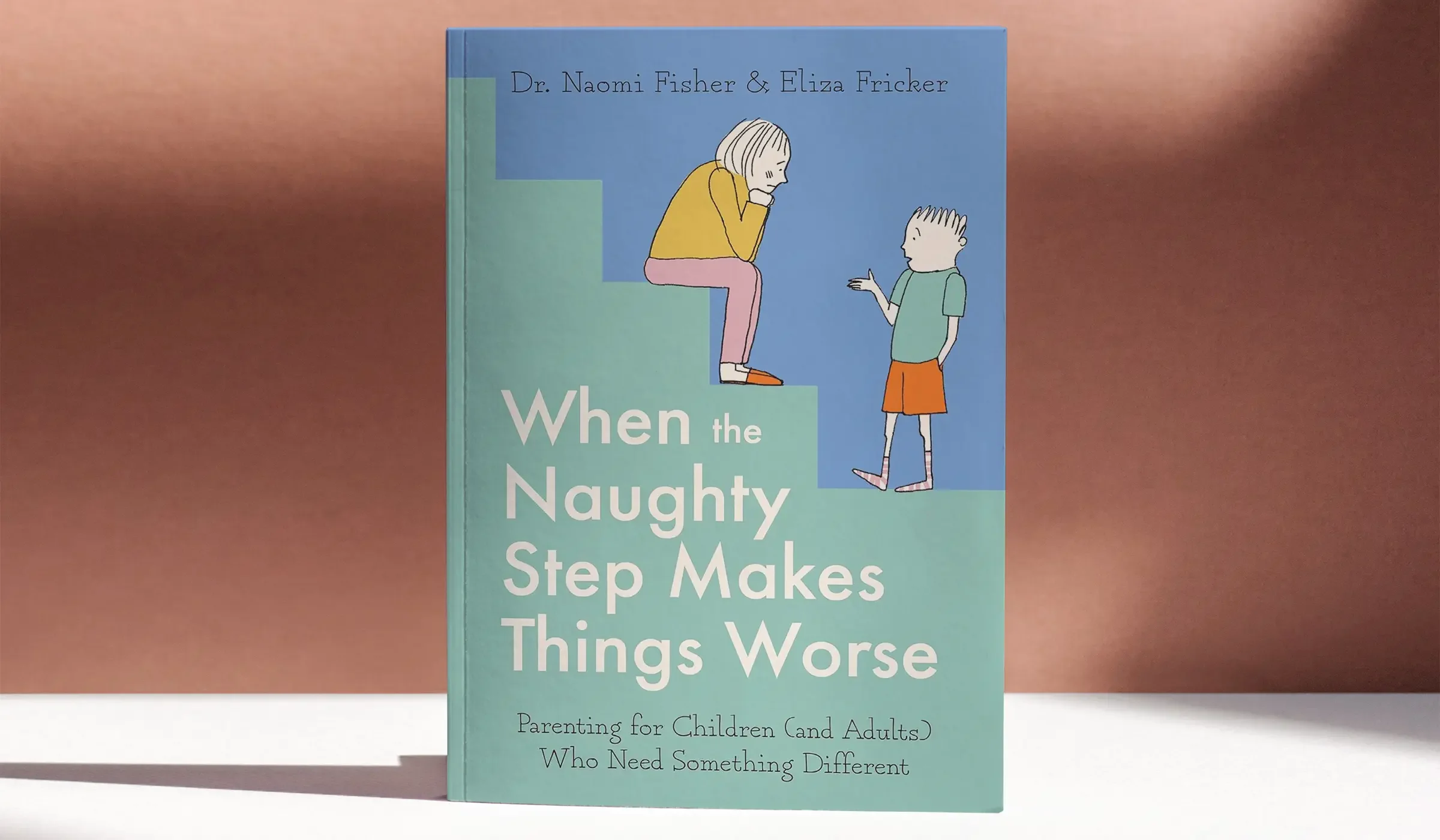

When the Naughty Step Makes Things Words by Dr Naomi Fisher & Eliza Fricker

When the Naughty Step Makes Things Worse is a compassionate, illustrated guide for families whose children (and adults) simply don’t respond to traditional “reward and consequence” approaches — including time-outs, naughty steps, or behavioural charts. The authors explain why behaviourist-style strategies often backfire, especially for pressure-sensitive or neurodivergent individuals, and offer a low demand, relational alternative aimed at increasing safety, choice, and connection rather than escalating conflict.

Readers consistently describe the book as reassuring, practical, and accessible — with clear explanations, useful examples, and exercises for everyday life. It doesn’t just question outdated parenting norms; it offers a compassionate way forward that can help repair relationships, reduce stress, and widen a child or adult’s capacity to engage over time.

This book is especially valuable for parents, carers, and professionals who want to understand why some approaches make things worse and how we might instead respond in ways that honour autonomy, co-regulation, and neurodiversity.