Understanding Neurodivergence!

A neuroaffirmative perspective

Neurodiversity describes the natural variation in how human brains develop and experience the world. There is no single right way for a brain to work. Differences in attention, learning, movement, communication, sensory processing and regulation are part of human diversity.

A core component of the Neurodiversity Paradigm is that it is both natural and important to have variations in neurological development and functioning with humans and we are not all meant to be the same. Differing neurologies include differing developmental trajectories. In most cultures, value has been placed on neuro-normativity and this has infiltrated how we conceptualise and understand neurodivergence and the experience of different neurotypes.

People who are neurodivergent differ from societal, conformist norms in how they experience the world, their ways of thinking and how their brains work. The neurodivergent umbrella includes Autistic people, AuDHers and ADHDers, dyslexic thinkers, dyspraxic individuals, PDA’ers, people with different language development pathways and many more.

To be neuroaffirmative means you value every brain type equally and view differences not deficits to be fixed, but as valuable variations of human ways of being. By understanding how a child’s nervous system and brain works, we can provide support by changing environments, systems, cultures and practices to meet their needs.

Being Autistic

A note on language - it is important to note that preferences in terminology frequently differ between members of the autism community, and that the preferences of the Autistic person with whom you are engaging should always be the first consideration. That said there are a number of widely preferred terms. Overwhelmingly, ‘identity first’ language is preferred by most Autistic people because they see being Autistic as integral to who they are, not as something they ‘have.’ We recommend consulting our Guide to Inclusive Language and Values, a living, evolving document that helps to ensure we are up to date and respectful of the community about whom we speak.

Sensory & social communication differences

Autistic children often experience differences in how they process sensory information and social communication. Sensory input such as sound, light, movement, or touch can feel more intense, unpredictable, or harder to filter. This can increase cognitive load and nervous system stress across the day, particularly in busy or noisy environments.

Social communication differences may include a preference for direct language, difficulty interpreting unspoken rules, and differences in how connection is expressed. Autistic communication is meaningful and valid and to be valued. Some Autistic children may be non, minimally or variably speaking using mouth words. We should always presume competence and understand that there is a vast range of means by which to communicate. Stimming (self stimulating) actions and activities (and thoughts) are the body and mind’s embodied sensory language — rhythmic movement, sound, or touch that supports regulation and expression. It enables flow and interdependent connection between Autistic people, other beings, and the sensory worlds of which we are all part.

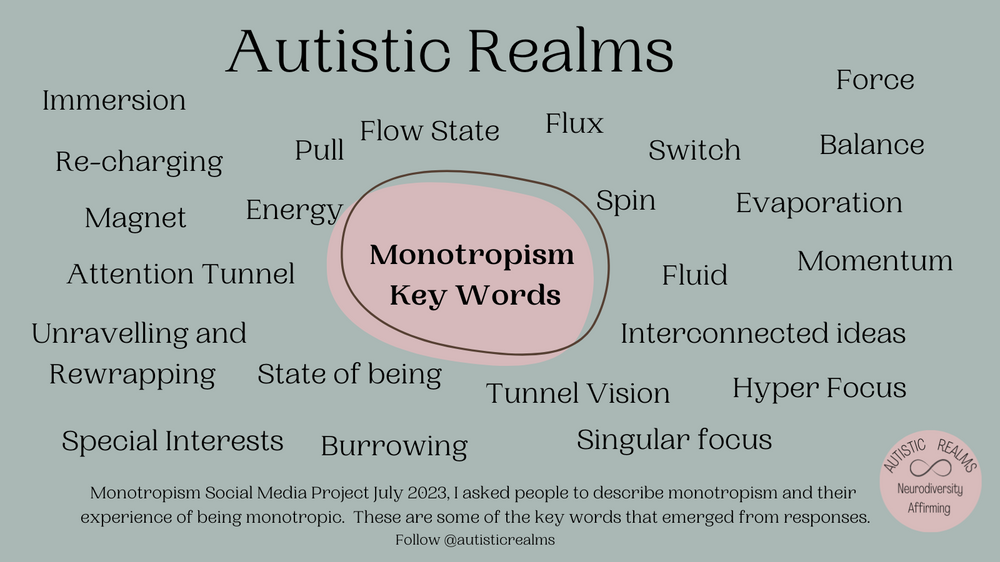

Monotropism

Monotropism is increasingly considered to be the underlying principle behind autism and is becoming more widely recognised, especially within autistic and neurodivergent communities. Fergus Murray, in their article Me and Monotropism: A Unified Theory (2018), describes montropism as, ‘resting on a model of the mind as an interest system’. They continue by saying; ‘we are all interested in many things, and our interests help direct our attention. Different interests are salient at different times. In a monotropic mind, fewer interests tend to be aroused at any time, and they attract more of our processing resources, making it harder to deal with things outside of our current attention tunnel‘.

Autistic /ADHD / AuDHD people are more likely to be monotropic (Garau et al., 2023). If you are monotropic, your attention may be pulled very strongly towards a specific focus, interest or sensory experience. This may mean things outside that attention tunnel get missed whilst the majority of your attention is directed towards something specific. Monotropic interests are often very intense and can be completely consuming. It may feel like you are deep diving; being hyper-focused may use all (or the majority) of your energy and attention resources affecting your mind and body. Some interests may be fleeting but still very intense.

How Autistic Children are Identified

Identification usually involves gathering a developmental history and understanding how the child experiences sensory input, communication, relationships, and the demands of daily life. The criteria contained in the American Journal of Psychiatry’s reference manual, the DSM-5 are largely considered to focus upon behaviours that an autistic person would exhibit when distressed, whereas a neuroaffirmative assessment focuses upon understanding the child’s profile and support needs rather than measuring deficits or compliance.

At present, there is no publicly funded, standalone autism assessment pathway for children in Ireland and, instead, an application for an Assessment of Need (AON) may be made where a parent or carer, school or other professional, believes that identification may be needed. As part of the AON process, an autism assessment may be performed or recommended. See our Critical Review of the AON system here.

There are a range of providers of private autism assessments and we recommend consulting our Guide to Choosing a Psychologist, for information on how to determine which professional is suitable for your child. The Children’s Clinic, Sandycove, are the original neuroaffirmative autism assessors in Ireland.

We recommend highly the Neurodiversity Affirmative Child Autism Assessment Handbook by Dr Kavanagh, Dr Day, Davida Hartman, Tara O’Donnell-Killen and Jessica K Doyle, for advice on what to expect from an autism identification process carried out by neuroaffirmative practitioners.

Autistic Burnout

Autistic Burnout is a state of exhaustion, when the demands of life exceed the mental or physical energy you have to deal with them.

As you try to cope with this, your energy depletes, and your body struggles to manage things that you may usually find easy.

The demands may be too much and you may not have support to cope with the demands, resulting in higher levels of stress.

Because you do not have the energy to manage the situation, you need time/ space/ tools to recover your energy. But if you are unable to get the opportunity to properly recover, your energy reaches 0, and you are in burnout.

Autistic burnout is an incredibly difficult experience where your brain is in overdrive and you always feel stressed.

Autistic educator Judy Endow describes Autistic Burnout as a “state of physical and mental fatigue, heightened stress, and diminished capacity to manage life skills, sensory input, and social interactions, which comes from years of being severely overtaxed by the strain of trying to live up to demands that are out of sync with our needs. ”Phung et al. (2021) interviewed Autistic young people who used words such as “exhaustion, feeling stuck, frozen and being entirely overwhelmed” to describe how burnout felt for them.

Arnold et al. (2023) says that “Autistic Burnout is a debilitating syndrome preceded by an overload of life stressors and the daily challenge of existing in a neurotypical world.” Their research and recent studies “show autistic people experience a combination of exhaustion, withdrawal and problems with their concentration and thinking. Burnout seems to be linked to the stress experienced by autistic people in their daily lives.”

Signs of burnout:

Key features of Autistic Burnout include changes in:

Cognition, executive function, memory, speech/communication, ability to cope, ability to do things once could do

Increased sensitivity to sensory stimulus, to sensory overload, to change to social stimulus

Increased autistic behaviour (e.g., stimming)

More frequent meltdowns/shutdowns

Chronic exhaustion You may find it harder or more overwhelming to do everyday things that you used to find easy (e.g., washing, dressing, sorting and tidying, preparing snacks).

You may be more forgetful and have difficulty remembering things people have told you, this can be really frustrating!

It may be harder to make choices, such as choosing what to eat, watch on TV or play with.

You may find sensory things such as different sounds / sights / smells / tastes / textures around you and the need for different movements either increased or decreased

You may experience more headaches, tummy aches or other physical symptoms.

You may feel constantly exhausted, or you may feel a bit like you have too much energy and feel restless and agitated.

Your sleep and diet may be affected, you may find that you are eating / sleeping more or less than usual.

You may be more emotional, more anxious, more tearful or angry but not really able to understand why.

You may struggle to see your friends as much. You may want to stay at home much more and feel unable to go out, including struggling to leave your room.

You may find that you need to work harder to focus on one thing at a time, you may feel like you want to spend all your time with your deep interests to help you manage, or you may lose interest in everything you once enjoyed as you feel too depressed and tired.

It is important to note that burnout may look similar to depression, but is different (and can occur at the same time).

The following are also signs of Autistic Burnout for children:

Changes to diet and eating

Changes to sleep patterns

Changes to sensory perception

Emotional changes: may be more tearful /connection-seeking/ angry /frustrated

Need for more autonomy and control

Executive functioning difficulties escalated

Recovery from burnout will look different for each individual, however, it is worthwhile to focus on what is regulating for your child’s nervous system and to centre their autonomy & equality.

Lived Experience of Autistic Person

“As an Autistic person, I experienced school and social environments as requiring constant effort. Much of my energy went into understanding expectations that were never explicitly explained. I learned to mask early, copying peers and suppressing my natural ways of communicating and regulating in order to fit in. Over time, this led to exhaustion and school burnout rather than increased confidence.

What helped was not being pushed to appear less autistic, but having adults who reduced pressure, made expectations predictable, and accepted my communication and regulation needs without judgement.”

Sorcha Rice

AuDHD PDA’er and Clinical Manager at Neurodiversity Ireland

Going through the process of my daughter’s identification made me realise that the way in which I thought about things or experienced things, was due to my own neurodivergence. My nervous system has lived in a state of constant stress for as long as I can recall, showing up in tummy problems, headaches, teeth grinding, sore muscles and skin picking. Autistic girls are much more likely to be missed, due to comparisons with stereotypes that do not fit and models of assessment based on male-only research. My preference for sameness (perfectionism), repetition (in my head), justice (appearing as rigidity), rejection sensitivity and sensory preferences (attention seeking!) were overlooked. As we strove to understand and support our daughters’ needs, it became obvious that I had never understood my Autistic self. I am also PDA and ADHD (as are my daughters) and believe passionately that early identification and support will prevent very many neurodivergent girls from entering the almost inevitable cycles of restricted eating, negative self image and low self esteem, masking to the point of collapse, self injurious and risk-taking behaviours and suicidal ideation.

Nessa Hill, CEO, Neurodiversity Ireland

ADHD

Sensory & executive functioning differences

Children with ADHD often experience differences in both sensory processing and executive functioning. Sensory input can be either under or overwhelming, and regulation can fluctuate across the day. Executive functioning differences may affect attention, nervous system regulation, working memory, task initiation and time awareness. Hyperactivity can show up both mentally and physically.

Attention in ADHD is interest based rather than effort based. When something is meaningful or engaging, focus can be deep and sustained. When tasks are externally imposed or lack relevance, initiation and follow through can feel genuinely impossible. Children who are ADHD will experience much greater instances of negativity from adults, which can result in poor self esteem.

Lived experience

Living with ADHD can feel like having a fast, curious brain in a world that expects consistency and linear productivity. There can be shame attached to forgetting, procrastinating, or struggling with organisation, even though these are neurological differences rather than personal failures.

Support that focuses upon regulation, reducing cognitive load, increasing autonomy and working with interest rather than against it makes a significant difference to wellbeing.

How ADHD is identified

Identification typically involves gathering information from home and school alongside clinical interviews. The questionnaires used for ADHD diagnosis may be considered to be slightly outmoded and male-centric and may risk missing female presentation. Diagnosis can support self understanding and access to accommodations. A neuroaffirmative approach recognises ADHD as a difference in regulation and executive functioning, not a behaviour or motivation problem.

There are currently limited options for ADHD identification in Ireland. CAMHS supports moderate to severe mental health challenges (as opposed to “just ADHD”) and will often refer autistic children onwards to a waiting list for a CDNT. There is no current, standalone public pathway for ADHD identification and very limited availability of private Child Psychiatrists.

How ADHD is supported

Children may be assisted by various forms or combinations of ADHD medication, which may only be prescribed by a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist. If you consider that medication may be required, it is important that your child’s identification is carried out by a Child Psychiatrist, in order to avoid the requirement to obtain a second assessment. Psychologists cannot prescribe medicine.

Information about ADHD medication for children (and their families) can be found in short videos by YouthMed which may be useful for explaining to children why it is needed and what it does.

Lived Experience of ADHD

ADHD..

Sorcha Rice

AuDHD PDA’er and Clinical Manager at Neurodiversity Ireland

Accessing ADHD medication for our 3 year old daughter was almost impossible, but life-changing. It gave her the opportunity to slow down, to access her senses and to participate more fully in life. Medicating a child for ADHD is incredibly stressful and involves many trials, errors, changes and stressful situations. The benefits vastly outweigh the preconceived negatives. Melatonin can be invaluable for children who are ADHD, every night or at times when it becomes a necessary support. The issue of ADHD medication is still shrouded in stigma and shame, whereas in our case, we believe it has saved our daughter’s life.

Dyslexia

The Delphi definition of dyslexia (2025) describes it as a set of processing difficulties that primarily affect reading and spelling, with challenges varying in severity across individuals. Dyslexia is a difference to be supported and accommodated, not a deficit to be fixed.

It is linked to differences in how the brain processes written language, particularly phonological (sound–symbol) information, and is not related to intelligence, motivation, or vision.

Globally, around 1 in 10 people are estimated to have dyslexia as a learning difference. With the right support, dyslexic children can thrive academically and often excel in areas such as design, science, entrepreneurship, art, and leadership.

Common Signs of Dyslexia in Children

Signs of dyslexia can vary, but parents may notice:

Difficulty learning letters, sounds, and spelling patterns

Slow or effortful reading

Trouble remembering sequences (e.g., numbers, days of the week)

Avoiding reading or writing tasks

Confusion with similar letters or words

Strong verbal skills or creative thinking

Note: Not all children show every sign—early observation and support are key.

Strengths Often Seen in Dyslexic Children

Many dyslexic children have unique strengths, including:

Creativity and imagination

Big-picture or systems thinking

Problem-solving and innovation

Visual-spatial reasoning

Oral storytelling and communication

Resilience and persistence

Recognising these strengths helps children build confidence while receiving the support they need.

Impact in school and learning environments

Dyslexia primarily impacts how written language is processed. Reading, spelling, and written expression may require more effort and time, particularly in environments that prioritise speed and accuracy. These difficulties can mask underlying strengths in comprehension, reasoning, creativity, and verbal expression.

School settings that rely heavily on written output can increase stress and negatively impact confidence if supports are not in place.

Lived experience

Many dyslexic children describe feeling intelligent but misunderstood. They often know what they want to say but struggle to get it onto the page. Repeated experiences of failure or comparison can lead to anxiety around learning, even when curiosity and intelligence are high.

How dyslexia is identified

Identification is usually carried out by an educational psychologist or specialist teacher through formal assessment of literacy and cognitive processing. Diagnosis can support access to accommodations such as assistive technology, reduced written demands, and alternative ways to show learning.

Children can be assessed for dyslexia once they are at least 6 years old and have had around 18 months of formal schooling (late in Senior Infants). Contrary to a common myth, children do not need to be 8 or older to be assessed.

Steps for Parents

Talk with the school

Share your concerns with your child’s teacher or learning support team. They can observe learning patterns and may already have informal screening data.Ask about a public assessment (NEPS)

The National Educational Psychological Service (NEPS) can provide assessments through schools. These are free but limited and usually require significant evidence of need.Arrange a formal dyslexia assessment

A psycho-educational assessment by a qualified educational psychologist or specialist provides a definitive evaluation.

Important: Ensure assessors meet recognised qualifications and follow guidance from Dyslexia Ireland and Neurodiversity Ireland.Get and use the report

The report should include recommendations for the school (teaching strategies, supports, and accommodations). Parents usually:

○ Arrange a meeting with the school principal or learning support team

○ Discuss implementing the recommended strategies

Note: School supports can be provided on a needs basis, so a formal report is not always required for interventions.

Support outside school

Workshops, tutoring, and reading support services can help children build literacy confidence. All literacy strategies should be Structured Literacy programmes based on the Science of Reading. Learn more: The Literacy School – Structured Literacy Guide

Available Accommodations for Dyslexia

Irish Exemption

In Ireland, Irish (Gaeilge) is compulsory. Children with significant literacy difficulties, including dyslexia, may qualify for an exemption from studying Irish.

To qualify:

● The child has received appropriate learning support

● Literacy difficulties are severe and ongoing

● Standardised test scores remain very low despite support

Important: A formal diagnosis is helpful but not always required. Parents apply through the school principal using the Department of Education form. If granted, the exemption certificate remains valid through primary and secondary school. Parents can appeal if an application is refused.

Learn more: Department of Education – Irish Exemption

Assistive Technology

NEEDS MORE INFO

Children with dyslexia may also benefit from:

Text-to-speech software

Audiobooks and digital reading tools

Word processors and spellcheck software

Mind-mapping or visual planning tools

Useful Resources

Lived Experience of Dyslexia

Dsylexia

CJay

Dairine Kennedy - podcast

Dyspraxia

Motor coordination and learning new tasks

Dyspraxia impacts motor coordination and motor planning. Children may take longer to learn new physical tasks and may need more repetition and explicit teaching. Everyday activities such as handwriting, dressing, using tools, or participating in sports can feel effortful and tiring.

Handwriting difficulties are common and may include poor letter formation, slow writing speed, or discomfort when writing for extended periods. These challenges are neurological and not a reflection of effort or motivation.

How dyspraxia is identified

Identification is typically carried out by an occupational therapist through a full functional assessment. This includes observing motor planning, coordination, daily living skills, and handwriting. Handwriting assessment forms an important part of understanding how dyspraxia impacts school participation.

Occupational therapy focuses on supporting participation, confidence, and adaptive strategies rather than forcing skills to look typical.

Lived Experience of Dyspraxia

Dyspraxia..

“Communication was top-notch and the final outcome was even better than we imagined. A great experience all around.”

Gestalt Language Processing

Language development through gestalts

Gestalt language processors develop language in meaningful chunks rather than single words. Children may use scripts, echolalia, or repeated phrases to communicate. These gestalts are not meaningless repetition but carry emotional and communicative intent.

Gestalts often serve a regulating function. Familiar phrases can provide safety, predictability, and emotional grounding, particularly in moments of stress or uncertainty.

How gestalt language processing is identified

Identification is based on observing how a child uses language in real life contexts rather than relying solely on developmental milestones. Speech and language therapists who understand gestalt language processing look at communication intent, regulation, and connection.

Support focuses on modelling language naturally, building safety, and expanding language without removing or discouraging gestalts.

Lived Experience of Gestalt Language Processing

“From my own lived experience, gestalts were deeply connected to safety and regulation. Certain phrases carried emotional meaning long before I could break them down into flexible language. Being allowed to communicate this way, without pressure to change or correct it, supported my sense of safety and connection.”

Sorcha Rice

AuDHD PDA’er and Clinical Manager at Neurodiversity Ireland

“Communication was top-notch and the final outcome was even better than we imagined. A great experience all around.”

AuDHD (Autistic and ADHD)

Despite the high co-occurrence, it wasn’t until relatively recently that AuDHD could be diagnosed. Prior to the release of the DSM-5 in 2013, the diagnostic criteria did not allow for co-diagnosis of autism and ADHD. They were considered mutually exclusive conditions.

AuDHD is a complex neurotype that cannot be reduced to its individual components of autism and ADHD. It is a unique way of perceiving, thinking, and engaging with the world that comes with both struggles and strengths.

Understanding AuDHD requires a holistic view of a person and how they interact. It means moving beyond the pathology paradigm to appreciate neurodiversity.

How gestalt language processing is identified

Identification is based on observing how a child uses language in real life contexts rather than relying solely on developmental milestones. Speech and language therapists who understand gestalt language processing look at communication intent, regulation, and connection.

Support focuses on modelling language naturally, building safety, and expanding language without removing or discouraging gestalts.

Useful Resources

People-First Approach

Everything we do is built around understanding your needs and helping you succeed—because when you thrive, so do we.

Long-Term Relationships

We’re not just here for the now. We love creating lasting relationships with our clients and growing with them over time.

Proven Process, Flexible Execution

We bring structure where it counts and adaptability where it matters. Our methods are clear, but always responsive.